Technological advances in organ transplantation have given hope to many patients with organ failure. However, the scarcity of organ donors remains a significant problem, resulting in many patients waiting for organ transplants each year with so few donor sources available. This shortage not only directly affects the survival of patients but also involves the social and ethical issue of the illegal human organ trade. Is it possible to find alternative resources?

In January 2022, a surgical team at the University of Maryland Medical Center transplanted the heart of a genetically modified pig to heart failure patient David Bennett, enabling him to live for nearly two months before he died from a swine virus infection. For xenotransplantation organ technology, those eight weeks were epoch-making, and the case caused an instant sensation while a consensus grew in the transplantation community on the use of pigs as an ideal human organ donor source.

Scientists are equally concerned about the risk of viral infection carried by the pigs themselves, which is particularly important when the necessary immunosuppressive drugs are given to patients undergoing transplantation, in addition to immune rejection, which is common in organ transplantation.

Recently, Professor Ralf R. Tönjes’ team at the Paul Ehrlich Institute in Langen, Germany, published a new study in the Journal of Virology demonstrating that gene editing could remove the PERV-C retrovirus genome from the pig genome, contributing to the virological safety of xenotransplants.

The potential risk of cross-species infection due to the presence of numerous viruses in pigs is an issue that must be considered when performing xenotransplantation. Among them, porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERVs) are RNA viruses with a high risk to humans that cannot be excluded by conventional measures such as sterile culture and screening. The three types of PERVs differ in their ability to infect, with PERV-A and PERV-B overcoming the species barrier and potentially infecting humans after transmission, while PERV-C retroviruses primarily infect pig cells, not human cells, but PERV-C can recombine with PERV-A to produce PERV-A/C, which in turn infects human cells.

This is why the haplotype SLAD/D breed of pigs, which does not have fully functional PERV-A and PERV-B genomes but may be carriers of the PERV-C genome, is currently selected as a transplant donor; therefore, it is necessary to characterize all genomic PERV-C loci in SLAD/D breed pigs.

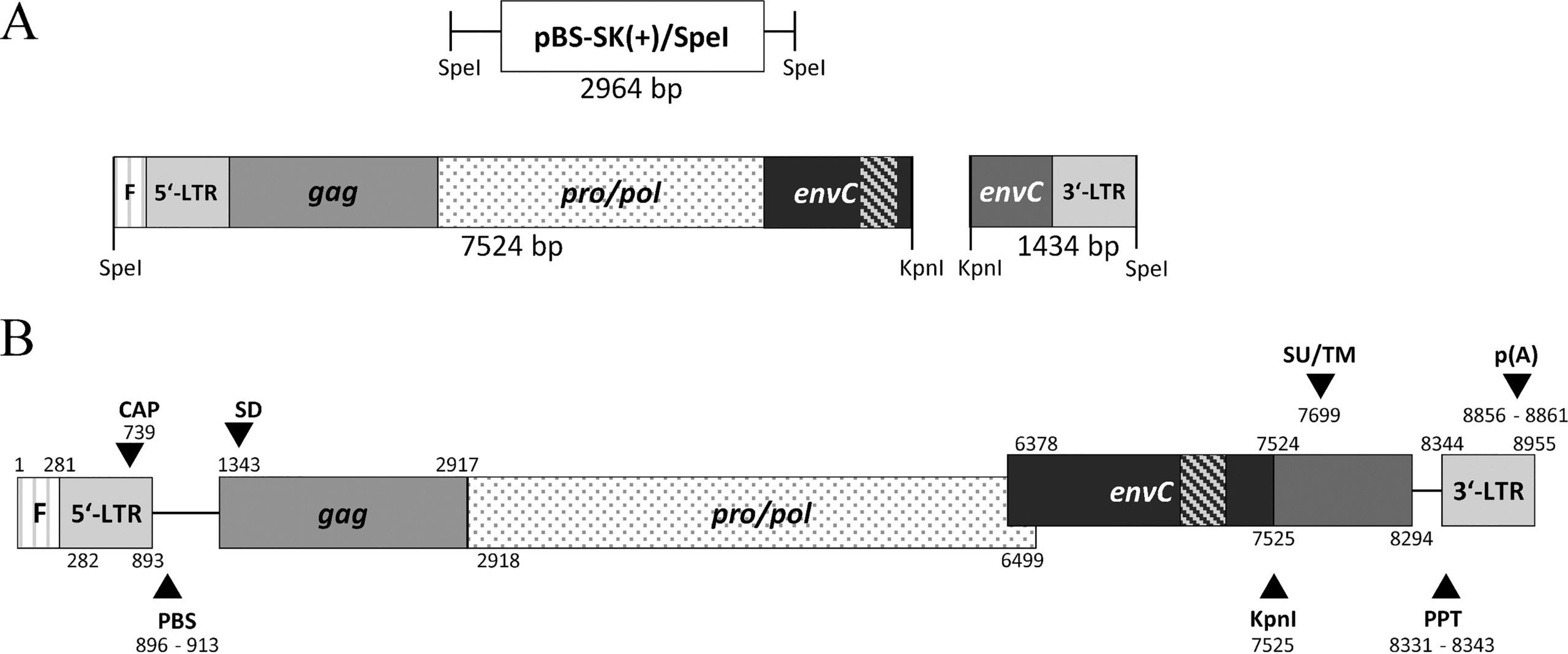

In this article, the researchers first constructed a phage lambda library using genomic DNA from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of SERV-C-positive haplotype SLAD/D pigs. They then screened the library for PERV-C with specific radiolabeled probes, isolated full-length PERV-C provirus clone #561, from which several full-length PERV-C proviruses were generated, and two clones, PERV-C (5634) and PERV-C (5683), were selected.

The researchers first examined the replication and infectivity of PERV-C (561) and compared it to PERV-C (1312), which had been identified as replication-competent. The PERV-C (5634) and PERV-C (5683) proviruses were transfected into ST-IOWA cells, and viral reverse transcriptase (RT) activity was detected nine days after transfection. This was four days earlier than the detection of PERV-C (1312). Two weeks after transfection, PERV-C (5634) reached a maximum of 210 mU/mL, and PERV-C (5683) reached a maximum of 256 mU/mL. This was 5-10 times higher than the positive control PERV-C (1312). At the end of the observation period, the RT activities of PERV-C clones were all in the range of 100 to 200 mU/mL, indicating that they can be stably propagated in cell culture.

Next, virus-free cell supernatants from transfected cell cultures were collected on day 20, and the infectivity of the PERV-C clone was detected by measuring the RT activity of the PERV-C clone and quantifying envC-specific viral RNA (vRNA) encapsulated in viral particles. qRT-PCR results showed that both PERV RT activity and PERV RNA were detectable. PERV vRNA was increasing in replication from day 7 to day 56, during which time the proviral envC DNA in infected ST-IOWA cells was detected by nested PCR. This demonstrated that PERV-C (5634) and PERV-C (5683) were highly replicative and infectious in vitro.

To verify the authenticity of recombinant PERV-C, its structure was confirmed by sequencing the PCR product. Both clones produced functional and infectious recombinant retroviruses. This indicates that this breed of pig contains at least one full-length PERV-C provirus. By chromosomal localization of the recombinant clone PERV-C (561), the researchers found that the chromosomal location was different from the previously validated PERV-C (1312) provirus.

Overall, PERV-C from haplotype SLAD/D pigs is highly replicative and infectious in vitro. However, these PERV-C loci can be knocked out by gene editing to reduce the risk of viral infection during xenotransplantation.

Although the overall level of animal welfare may be compromised from an animal welfare standpoint, xenotransplantation is a humanitarian measure to relieve the suffering of patients. It is consistent with favorable principles in medical ethics. As technology advances, we look forward to the day when they can become safe donors to save the lives of more patients.

Reference

1. Rodrigues Costa, Michael, et al. “Isolation of an Ecotropic Porcine Endogenous Retrovirus PERV-C from a Yucatan SLAD/D Inbred Miniature Swine.” Journal of Virology 97.3 (2023): e00062-23.