The receptors, found in so-called elite controllers who don’t need medications to keep the virus in check, suggest a new path toward immunotherapy.

Researchers trying to develop new treatments, or even a cure, for HIV have searched for strategies by looking to the tiny percentage of the HIV-positive population with a rare gift: the ability to naturally keep the virus’s numbers low, without a need for antiretroviral therapies. In doing so, researchers have discovered differences in the behavior of immune cells between these “elite controllers” and patients who require drugs, suggesting it could be possible to fine-tune the immune responses of noncontrollers to help them fend off the virus.

Now, researchers led by Stephanie Gras of Monash University in Victoria, Australia, report how an unusual T-cell receptor found in the CD4+ T cells of some elite controllers is able to recognize low levels of HIV and mount a response. Gras says the finding, reported today (June 8) in Science Immunology, may be good news for the prospect of developing an immunotherapy to rev up the CD4+ attack on HIV.

Now, researchers led by Stephanie Gras of Monash University in Victoria, Australia, report how an unusual T-cell receptor found in the CD4+ T cells of some elite controllers is able to recognize low levels of HIV and mount a response. Gras says the finding, reported today (June 8) in Science Immunology, may be good news for the prospect of developing an immunotherapy to rev up the CD4+ attack on HIV.

The research team has added “an additional cornerstone in our understanding of how HIV controllers maintain virus control,” says clinical infectious disease specialist Andrea De Maria of the University of Genoa in Italy who was not involved in the study. He adds that the findings “could open the possibility of immunotherapy, a little bit like what is being done right now against tumors with CAR T cells.”

Fewer than 1 percent of HIV-positive people are elite controllers. The new study builds on earlier work in which the same research team found that controllers were far more likely than noncontrollers to have receptors on some of their CD4+ T cells that are known as “public” receptors. Most T-cell receptors (TCRs) are like locks that only activate their cells if they come in contact with a matching human leukocyte antigen (HLA) bearing a bit of protein from a virus or other potential threat. In contrast, public receptors can recognize an array of HLAs. What’s more, notes Gras in an interview released by Science Immunology, one of the public receptors was found in multiple people. “We all have about 100 million different TCRs, and to find the same receptor in two individuals is very rare; we found the same TCR in six different individuals, and all those individuals were HIV controllers,” she says. “And so we thought there must be something special about these TCRs.”

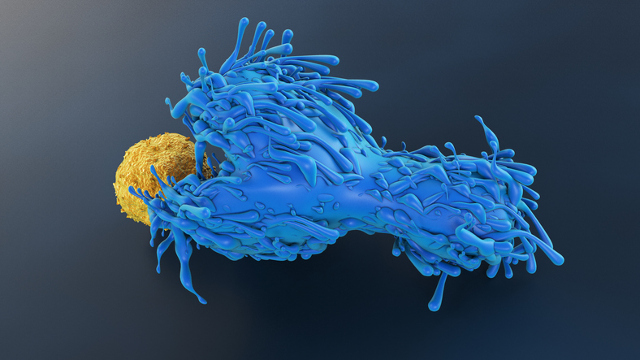

In the current study, Gras and colleagues took a look at the public TCRs’ effects on immune response to infection, and what enables them to be activated by multiple HLAs. In culture, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells armed with one of the public TCRs effectively recognized and killed HIV-infected dendritic cells, the team found.

The researchers also determined the structure of the complexes formed when public TCRs interact with different HLAs holding bits of protein from HIV, and found that each TCR’s contact was primarily with the HIV-derived peptide rather than with the HLA itself.

“If we think in terms of transfer and in terms of therapeutics, this is really good, because that means we can use this TCR transfer to T cells in different individuals who have different genetic backgrounds,” Gras tells The Scientist. Her group plans to begin testing the idea soon in mice by genetically modifying their T cells to produce public TCRs, and see whether such an immunotherapy might enhance the animals’ ability to fend off HIV.

“If we think in terms of transfer and in terms of therapeutics, this is really good, because that means we can use this TCR transfer to T cells in different individuals who have different genetic backgrounds,” Gras tells The Scientist. Her group plans to begin testing the idea soon in mice by genetically modifying their T cells to produce public TCRs, and see whether such an immunotherapy might enhance the animals’ ability to fend off HIV.

“If developed, it could hopefully provide some help,” comments De Maria. But he cautions that public TCRs by themselves don’t explain the elite controller phenomenon, and may not be able to mimic that protection, because “there’s not one single mechanism that probably contributes to HIV control.”

“Much of the focus in therapeutic vaccine development has been on the CD8+ T cell responses. This particular paper sheds more light on the role of CD4+ T cells in contributing to control, and this may be a new dimension to consider in designing therapeutic vaccines” for HIV, says Peter Hunt, a translational HIV researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the study. He notes, though, that CD4+ response is a “double-edged sword,” because “while an effective CD4+ T-cell response is important for killing infected cells and supporting HIV-specific CD8+ cells, the HIV-specific CD4+ cells are some of the fattest targets for direct HIV infection of cells.” They become vulnerable to infection when they proliferate at a site of infection and produce HIV-specific receptors, Hunt says.

An alternative route to pursue would be to incorporate the HIV-derived peptide that elicited the strong T-cell response—a highly-conserved chunk of the capsid protein Gag293—into a vaccine, says Joel Blankson, who studies natural control of HIV infection at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and was not involved in the study. “I think immunization with the epitope would be effective, but if people didn’t respond, then maybe the second option would be to do the transduction of the public T-cell receptors in those patients who did not respond.”

Source: https://www.the-scientist.com/daily-news/public-t-cell-receptors-from-resistant-people-fend-off-hiv-48401