In a recent study, researchers from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai show that a new cancer immunotherapy that uses one type of immune cell to kill another type of immune cell instead of attacking the tumor cells directly can elicit a powerful anti-tumor immune response that shrinks ovarian, lung, and pancreatic tumors in preclinical disease models. The findings are published in the November 1, 2022 issue of Cancer Immunology Research in a paper titled “Targeting Macrophages with CAR T Cells Delays Solid Tumor Progression and Enhances Antitumor Immunity”.

Most solid tumors suffer from severe infiltration by a different type of immune cell called a macrophage. Macrophages help tumors grow by preventing T cells from entering tumor tissue, which prevents chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells and the patient’s own T cells from destroying cancer cells.

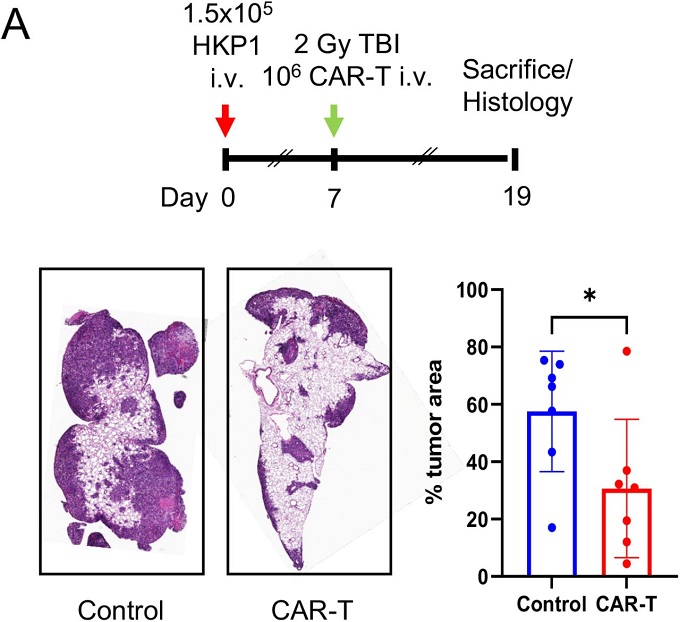

To address this immunosuppression problem at its source, these authors genetically modified T cells to express a CAR that recognizes the macrophage surface molecule F4/80. When these CAR-T cells encountered macrophages residing in the tumor, they were activated and killed the macrophages residing in the tumor. Treatment of mice with ovarian, lung, and pancreatic tumors with these macrophage-targeting CAR-T cells shows a reduced number of macrophages residing in the tumors, shrunk tumors, and prolonged survival.

Killing the macrophages residing in the tumors allowed the mice’s own T cells to enter and kill the cancer cells. These authors further confirmed that this anti-tumor immune response is driven by the release of the cytokine interferon from these CAR-T cells.

Dr. Brian Brown from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, the co-corresponding author of the paper, said that the initial goal was simply to use CAR-T cells to kill immunosuppressive macrophages, but they found that these cells also boost the tumor immune response by releasing this powerful immune-promoting molecule. It’s just like hitting two birds with one stone.

Shifting CAR’s position from cancer cells to macrophages residing in tumors has the potential to address another key hurdle to successfully eliminating solid tumors with CAR-T cells—most proteins are found both on the surface of cancer cells, and on that of healthy tissue, so few can be used to directly target cancer cells in solid tumors without damaging healthy tissue.

The immunosuppressive macrophages found in tumors are very similar in different types of cancer, but very different from those found in healthy tissue. This has led to a great deal of interest in macrophage removal agents for cancer therapy, but the methods developed to date have had limited success in clinical trials.

Dr. Miriam Merad from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, the co-corresponding author of the paper, introduced their molecular studies of human tumors, which have revealed that macrophage subpopulations are present in human tumors but not in normal tissues, and they are similar across tumors and across patients. He predicted that CAR-T cells targeting macrophages may be a broad way to target different types of solid tumors and improve immunotherapy.

Next, these researchers will further investigate tumor macrophage-specific CARs and try to generate a humanized version of the genetic instructions, thus introducing them into the cancer patient’s own T cells.

Reference

1. Sánchez-Paulete, Alfonso R., et al. “Targeting macrophages with CAR T cells delays solid tumor progression and enhances antitumor immunity.” Cancer Immunology Research 10.11 (2022): 1354-1369.